Lorelei and The Laser Eyes: An Indie Masterpiece

- Brothers In Gaming

- Mar 10, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Jul 12, 2025

For our first article of 2025, we played Lorelei and The Laser Eyes. Simogo's latest game blends intricate puzzles, surreal storytelling, and Italian cultural references into a bold indie masterpiece.

We have wanted to write about puzzle games for a while, primarily to answer the question: “What makes a great puzzle game?”. Despite playing several acclaimed titles — Cocoon, The Talos Principle, Superliminal, The Witness, We Were Here Together, Machinarium, and many others — none inspired us to write until we played Lorelei and The Laser Eyes ("Lorelei" for the remainder of the article).

When the game launched in May 2024, it flew under the radar. We chose the game because online reviews were very positive. Plus, we were captured by its unique art style and intriguing references to Italian culture (Renzo Nero, anyone?). We played before the Game Awards, and when it was nominated for Best Independent Game, we weren’t surprised at all.

Overview of Lorelei

How can Lorelei be summarized? It’s a surreal, nonlinear puzzle adventure set in a European hotel. Players follow a woman entangled in an obscure narrative that only fully reveals itself at the very end. The game’s core loop blends exploration, document collection, and puzzle solving, making it one of the most rewarding puzzle games we have played in a long time.

More than anything, we think Lorelei captures the essence of independent games and why they are gaining more attention in recent years: in the end, they don’t have to please everyone. Below is a compelling interview with the development team on the topic, where Jonas Tarestad sums it up well:

“I think mainstream culture today is so insanely anxious. So eager to please everyone. You end up with a result pleasing no one instead.”

Simogo: The Studio Behind Lorelei

Before diving into Lorelei's analysis, we wanted to briefly talk about Simogo's history in gaming.

Who is Simogo?

Simogo is a 15-year-old gaming studio based in Malmö, Sweden. Since 2010, the studio has operated with only two core employees — the founders Simon Flesser and Magnus Gardebäck — while collaborating with various partners depending on each project's needs.

One fascinating aspect of Simogo’s journey is how they transitioned from developing premium mobile games to creating console and PC games. From 2010 to 2015, they released premium iOS games like Kosmo Spin, Bumpy Road, Beat Sneak Bandit, Year Walk, Device 6, The Sailor’s Dream, and SPL-T. However, their two most recent titles — Sayonara Wild Hearts (2019) and Lorelei and The Laser Eyes — launched first on console and PC.

This shift highlights how much the premium mobile game landscape has changed over the past 15 years. As noted by Simogo in a 2017 blog post:

“The ease of mobile game development drew us to making iPhone games back in 2010. But, it’s getting increasingly financially unviable, tiring, and unenjoyable for us to keep making substantial alterations for new resolutions, guidelines, and what have you, as they seem to never end. [...] So, as you have probably understood by now, our current game in development, 'Project Night Road', is indeed a console game.”

This frustration, combined with creative possibilities offered by console platforms, led to Project Night Road — which later became Sayonara Wild Hearts.

Early Innovation

Simogo’s signature creativity was evident from the start. For instance, Bumpy Road (2011) is a 2D platformer where players move the road under the car rather than controlling the car itself — a simple yet innovative mechanic.

From Year Walk (2013) on, Simogo began exploring darker themes, text-based puzzle-solving, and folklore-inspired narratives. These elements became foundational in their later works. Sayonara Wild Hearts marked their boldest departure from traditional puzzle games, blending rhythm-based gameplay with vivid pop aesthetics. The game’s self-described genre of “pop album video game” reminds us of Rez, which we’ve mentioned in a previous article about Mizuguchi's synesthetic approach to gaming.

Despite shifting platforms, Simogo’s games consistently receive critical and public acclaim. Excluding The Sailor’s Dream (Metacritic 74), all their games have Metacritic scores of 86+. Beat Sneak Bandit and Device 6 surpass 90.

Game Design and Narrative Aspects

The rest of the article focuses on the design and narrative aspects of Lorelei that we loved the most. We aim to convey a holistic view of our ideas by reading it in full; however, if you are interested in a specific aspect of the game, feel free to jump to the related chapter!

Game Design

How Lorelei Bridges Puzzle Game Sub-Genres

Before diving into Lorelei, let’s discuss puzzle games in general. Generally, puzzle games fall into two categories:

Mechanic-driven puzzle games (e.g., Portal, The Talos Principle)

Logic-driven puzzle games (e.g., The Witness, Lorelei)

Even within the logic-driven genre, Lorelei stands out. While The Witness offers self-contained puzzles solvable without external hints, Lorelei is a contextual puzzle game with clues scattered across the world. Simogo borrows the onboarding philosophy from mechanic-driven games, gradually introducing players to the game’s logic.

This approach makes Lorelei surprisingly accessible, even to players who typically avoid puzzle games — a testament to Simogo’s thoughtful design.

General Approach in Mechanic-Driven Games

To understand Lorelei’s onboarding design, it’s helpful to look at how mechanic-driven games work. For example, in Portal, the first level teaches players two basic mechanics: placing boxes on buttons to open doors and creating traversable portals.

After this introduction, the game presents a level that combines these mechanics, validating that the player has understood the concepts. This creates a gate that players must overcome to proceed, giving them both a challenge and a clear objective.

Another critical element in mechanic-driven games is the balance of hints. Hints can be communicated in various ways: through text, voice-over, dialogue, level design, or camera framing. For instance, in a puzzle game I (the game design brother) have been working on, the first puzzle provides clear hints through in-game text and voice-over, while the second puzzle uses level design to suggest that the player should shrink themselves to proceed.

Lorelei's Approach

Lorelei combines the best of both worlds by integrating the gradual introduction of mechanics from mechanic-driven games with the logic-driven puzzle design of games like The Witness. This hybrid approach makes the game accessible while maintaining depth and complexity.

Below, we show how the onboarding works. If you want to play the game, you might want to skip it :)

!SPOILER ALERT!

The first puzzle serves as a tutorial, teaching players the core gameplay loop: gather information and use it to deduce solutions. At the start of the game, the player receives a letter with "the year" underlined in red, followed by a locked door requiring a 4-digit code. Nearby, they also find a second letter with "1962" and "next year," underlined in red. This prompts the player to deduce that the code is 1963 ("Find the year" + "1962" + "Next year" == "1963").

With this approach, Simogo hits two birds with one stone. It teaches players how to think within the game’s logic and demonstrates how hints are integrated into the world. By the time players encounter more complex puzzles, they’re already familiar with the game’s rules and expectations.

!SPOILER ALERT OVER!

Additionally, we find Lorelei's level design approach interesting and unique.

While most puzzle games follow a linear progression — solving one puzzle unlocks the next, increasingly difficult one — Lorelei adopts a more exploration-oriented core loop:

Explore: Wander the hotel, uncovering new areas and clues.

Find Documents/Objects: Collect items that provide hints or contain puzzles themselves.

Solve Puzzles: Understand which gathered information is relevant to a specific puzzle and solve it.

This structure encourages non-linear thinking as players must connect information from different parts of the game. For example, a document found early on might hold the key to solving a puzzle encountered hours later. This design choice keeps the game fresh and engaging, even over its 20+ hour runtime.

See below for an example of the skills the game requires from the player.

! SPOILER ALERT!

A prime example is the Roman numeral puzzle. About halfway through the game, players encounter three doors with pads displaying Roman numerals of varying lengths. Initially, the solution isn’t obvious. However, after exploring other areas and revisiting documents, players might realize that a book collected at the start contains the necessary Roman numerals. The solution was there all along—players just needed to connect the dots.

! SPOILER ALERT OVER!

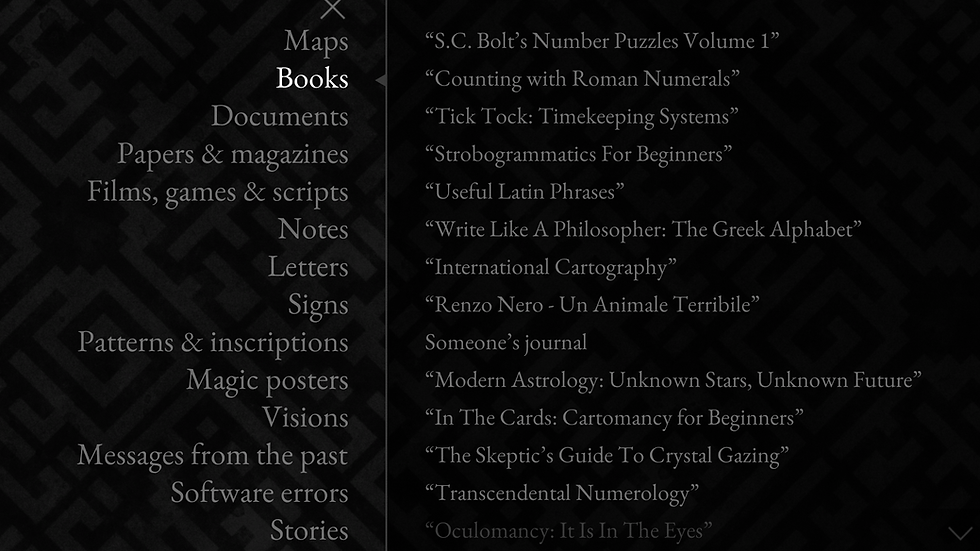

Documents as Game Design Pillar

Documents play a central role in Lorelei’s design. The game features a vast array of documents that players can collect and consult at any time. These documents are integral to solving puzzles and unveiling the game's narrative.

Simogo has carefully designed them to serve multiple purposes, including:

Some documents contain puzzles like mathematical riddles or cryptic drawings, and solving these provides needed information to progress (such as unlocking a door).

Others provide straightforward clues, often by underlining or highlighting specific parts of the text.

Some require players to interpret the information and connect it to the game world. For instance, a document might reference a location or object that players must find and interact with.

Others function as maps or guides, directing players to specific areas or puzzles within the game.

The variety and complexity of these documents ensure that players remain engaged, even after hours of play. Moreover, they are seamlessly integrated into the game’s lore, making the world feel cohesive and immersive.

Fixed Camera

One of Lorelei’s most distinctive features is its fixed camera system. Unlike modern games that allow players to control the camera freely, Lorelei uses pre-set camera angles that don’t change dynamically.

This design choice serves two main purposes:

Game Design. Many of Lorelei’s puzzles rely on specific camera angles to frame clues or hide information. A dynamic camera would disrupt this careful design. Additionally, the fixed camera permits Simogo to control what the player sees, ensuring that important details are visible.

Artistic Style. The fixed camera draws inspiration from cinema, particularly classic films where the director controls the viewer’s perspective, enhancing the game’s mood and aesthetic.

To mitigate the limitations of a fixed camera, Simogo shifts to a first-person perspective for specific puzzles. This allows players to manipulate the camera and interact with objects more directly. This ensures that the fixed camera never feels restrictive.

Overall, we loved this choice. It makes sense from a design and artistic point of view. Plus, it is, for us, a very nostalgic choice. Having grown up with 90s and early 2000s games (like Resident Evil and Metal Gear Solid), that was a time when the fixed camera was much more common. Simogo likely wanted to evoke a similar feeling, and they totally succeeded.

Randomized Puzzle Solutions

Another innovative design choice is the randomization of puzzle solutions. To prevent players from finding solutions easily online, Simogo randomized elements of the puzzles.

! SPOILER ALERT!

In the 1957 Room puzzle, players must identify which four out of ten pictures correspond to the numbers "1", "9", "5", and "7." Each player's correct combination of pictures is randomized, forcing them to engage with the puzzle’s logic rather than relying on external guides.

! SPOILER ALERT OVER!

One-Button Design

Simogo’s decision to use a one-button control scheme nods to classic point-and-click games while simplifying the player’s experience. With only two inputs—movement and a single button press—players can perform multiple actions: move the character, open the contextual menu, or interact with objects.

This minimalist approach has several benefits:

Accessibility: The simple controls make the game accessible to players of all skill levels, removing any barrier to entry.

Focus on Puzzles: By limiting actions, Simogo ensures that players concentrate on solving puzzles rather than mastering complex controls.

Creative Constraints: The one-button design compelled Simogo to think creatively about how to design puzzles within these limitations, resulting in unique gameplay mechanics.

For example, many puzzles require players to interact with specific objects, which then shifts the game into a "Focus Mode" where players can examine and manipulate the object in detail. This design choice enhances immersion and keeps the puzzles varied and engaging.

The Narrative

Meta-Story and Meta-Theatre

One of the most intriguing aspects of Lorelei and The Laser Eyes is its meta-narrative—a story existing within multiple layers of reality. The game doesn’t just tell a story; it plays with the very nature of storytelling, blurring lines between what is real, what is imagined, and what exists purely within the game’s internal logic.

At its core, Lorelei features two simultaneous meta-narratives:

The Player’s Story: The narrative players experience as they explore the hotel and solve puzzles is itself a construct within the mind of one of the game’s characters. This creates ambiguity—are the events real, or are they a figment of the character’s imagination?

Renzo’s Play: Scattered throughout the game are script pages revealing a play written by Renzo Nero, a central character. This play not only serves as a fictional work within the game but also as a meta-commentary on the nature of reality and illusion. Renzo aims to bring this play to life, further blurring boundaries between the game’s narrative and the "real" world.

These layers of storytelling create a narrative labyrinth where players constantly question what is real and what is imagined. The game shifts seamlessly between these layers, creating disorientation mirroring the hotel’s surreal atmosphere.

Meta-narrative is not new in gaming, but Lorelei elevates it by embedding it deeply into both gameplay and story. A recent example of meta-narrative in gaming is Silent Hill 2, where the protagonist’s reality is distorted by guilt. However, Lorelei goes further by weaving multiple layers of storytelling into its puzzles, environments, and documents.

We don’t want to overwhelm the article with information unrelated to gaming, but for any literature fans, meta-narrative and specifically “metateatro” is common in Luigi Pirandello’s novels and plays. In his works, plays often exist within plays, adding complexity to the narrative. More recently, Murakami has used similar devices in works like 1Q84 and Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World.

We could continue rambling about this, but we’ll stop for the sake of consistency! If you like the topic, reach out to continue the conversation :D

The Italian References

The game’s meta-narrative is enriched by numerous references to Italian culture, adding depth and texture to the story. These references are not superficial nods; they are integral to the game’s themes and atmosphere.

Renzo Nero

The name Renzo Nero is a clear Italian reference, and its duality with Lorelei Weiss is central to the game’s themes. "Renzo" is a common Italian name associated with Renzo Tramaglino, the protagonist of I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed) by Alessandro Manzoni. This classic Italian novel explores themes of fate, struggle, and love, which resonate with Lorelei’s narrative.

The contrast between "Nero" (black in Italian) and "Weiss" (white in German) reinforces the game’s preoccupation with duality—truth and illusion, light and darkness, reality and fiction. This duality is reflected not only in characters but also in the game’s visual and narrative style.

Italian Neorealism and the Game's Aesthetic

The visual and narrative style of Lorelei clearly shows traces of Italian neorealism, a cinematic movement emerging in the mid-20th century. Known for stark black-and-white cinematography and non-professional actors, Italian neorealism often blurred the line between reality and dream—a theme central to Lorelei. Directors like Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni explored similar themes in their films, creating worlds where reality is constantly shifting and uncertain. The game’s use of black-and-white visuals and fragmented, dreamlike storytelling evoke classic Italian films like Ladri di Biciclette (Bicycle Thieves) by Vittorio De Sica.

The game also features various fictional films, some carrying echoes of classic Italian cinema, with many titles hinting at "giallo" films (a genre of Italian crime and mystery movies). The game’s surreal, fragmented storytelling and dream logic are reminiscent of psychological horror films like Profondo Rosso (Deep Red) and Suspiria by Dario Argento. These films, much like Lorelei, use visual abstraction and unsettling atmospheres to create worlds where reality constantly shifts.

Santa Lucia: An Italian-Swedish Connection

One intriguing reference in the game is to Santa Lucia, a figure who holds significance in both Italian and Swedish culture. In Italy, Santa Lucia is a Catholic saint associated with light and vision, celebrated especially in Sicily. Legend depicts her holding a golden plate containing a pair of human eyes, offered to the viewer—a symbol of her devotion and sacrifice.

In Sweden, Luciadagen (Saint Lucia’s Day) is a major festival of light in the winter's darkness. Given Lorelei’s themes of vision, perception, and light, this reference is likely intentional.

Scattered Italian Words and Phrases

Throughout the game, players encounter Italian words and phrases like "Signorina" (Miss in Italian), reinforcing the European, old-world atmosphere of the setting. These linguistic touches add authenticity and immersion, evoking a remote, mysterious location. For fans of Italian literature, these references might evoke works like Il Nome della Rosa (The Name of the Rose) by Umberto Eco, where Latin phrases enrich the sense of medieval mystery and history. In Lorelei, the use of the Italian language serves a similar purpose, enhancing the atmosphere and thematic complexity.

Conclusion

As you can tell from the article, we loved Lorelei and The Laser Eyes. In our opinion, it is a masterclass in puzzle design and narrative storytelling, showcasing Simogo’s ability to innovate within the indie game space. Their decision to blend exploration, document-based puzzle-solving, and a fixed camera system creates a uniquely immersive experience that feels both nostalgic and refreshingly modern.

What sets Lorelei apart is its unwavering commitment to its vision. The game doesn’t try to cater to everyone—instead, it embraces its niche appeal, offering a deeply rewarding experience for those willing to engage with its complexities.

In a gaming landscape often dominated by trends and mass appeal, we believe Lorelei and The Laser Eyes stands out as a true piece of art. It reminds us that games don’t have to please everyone—they just need to resonate deeply with those who engage with them. For players who enjoy cerebral challenges, rich narratives, and a touch of the surreal, Lorelei is an unforgettable journey that lingers long after the final puzzle is solved! We totally recommend it.

Comments